February 13, 2020 by John Fernandez

Genetic Testing for Cancer: Facts and Benefits

Your father had colon cancer at age 48 and your paternal aunt died from ovarian cancer. You’re a healthy, 30-year-old man. Should you consider having a genetic test for Lynch syndrome?

What if you just received a diagnosis of breast cancer at age 55 and are not yet post-menopausal? Would it be helpful to know if your cancer were related to mutations in the BRCA1, BRCA2 or other identified genes that increase the risk for cancer?

Regardless of what the people in these scenarios would decide, one thing is clear: They would need genetic counseling to understand the sometimes complex issues involved before making an informed choice about genetic testing.

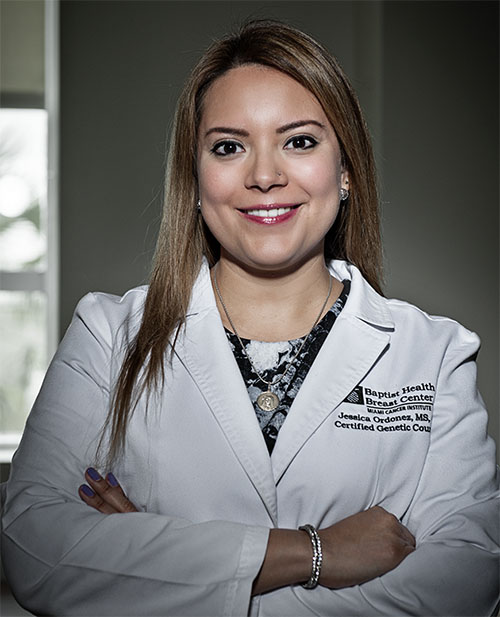

About 12 times a week, Jessica Ordonez (pictured at left), a certified genetic counselor with Miami Cancer Institute at Baptist Health South Florida, meets one-on-one with patients who have been referred by physicians to consider genetic testing. Some have cancer; others may be at increased risk for it due to a family history.

About 12 times a week, Jessica Ordonez (pictured at left), a certified genetic counselor with Miami Cancer Institute at Baptist Health South Florida, meets one-on-one with patients who have been referred by physicians to consider genetic testing. Some have cancer; others may be at increased risk for it due to a family history.

In the 90-minute session, Ordonez explains what genetic testing is, what information it can offer and how that information may be used in a treatment plan or to prevent cancer from developing. “I discuss the patient’s concerns and expectations. And the timing — is this timing right for testing?” Ordonez said. “Once you know, you can’t go back.”

Potential Implications of Testing

Most people referred opt for genetic testing when they understand the benefits, though they may delay the test for some reasons. For example, they may wait until they’re ready to manage the potential medical implications of a positive test result, or they may wait until purchasing life, disability or long-term care insurance. For people concerned that the testing information could be used against them, Ordonez explains the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008. Congress passed GINA to protect people from genetic discrimination in employment and health insurance.

Ordonez also helps people who already had a genetic test before they fully understood the ramifications. “We get people who were tested and they’re blindsided by the information. It might not make sense to them yet,” she said. In these cases, it is often helpful have a post-test genetic counseling session to fully address the results for the patient’s health and that of their family members. (For detailed information, check out the National Cancer Institute’s genetic testing fact sheet.)

Genetic testing has expanded and grown more sophisticated in the 20-plus years since scientists began isolating the genes associated with Lynch syndrome, and then breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Today, a panel of more than two-dozen cancer-susceptibility genes can be analyzed for mutations in one simple test. Most frequently, it’s a routine blood sample, but saliva or cells from the inside of the cheek also may be used.

“By no means do we know the full story of these genes,” Ordonez said. “There is still a lot to be learned.”

Ordonez relies on the latest evidence-based guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to counsel patients and help them decide which panel of genes is the appropriate test for them. The NCCN is a nonprofit alliance of leading cancer centers, whose experts update treatment and testing guidelines based on evolving research and discoveries.

“A gene is like a book; you read it,” she said. “Instead of reading one gene at a time, new technology allowed us to read multiple genes at once.”

The Impact of Angelina Jolie’s Story

In 2013, Angelina Jolie brought genetic testing and its impact to the forefront by sharing her story in a New York Times opinion piece, headlined My Medical Choice. Her mother died of breast cancer at age 56. After testing positive for the BRCA1 mutation, putting her at high risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, Jolie opted to have a double mastectomy and, two years later, an operation to remove her ovaries.

This preventive care substantially reduced her risk for breast and ovarian cancer. “I choose not to keep my story private because there are many women who do not know that they might be living under the shadow of cancer,” she wrote. “It is my hope that they, too, will be able to get gene tested, and that if they have a high risk they, too, will know that they have strong options.”

A native of Colombia, Ms. Ordonez studied at the University of Michigan, earning undergraduate degrees in molecular biology and literature before completing her master’s degree in genetic counseling. She started working at Baptist Health last year. In the past 14 years, some 4,000 patients were tested through Baptist Health’s Genetic Risk Education Service, founded by cancer genetic educator Rae Wruble, R.N.; the counseling component was added with Ms. Ordonez’s hiring to form the Genetic Risk Education & Counseling Services.

Center for Genomic Medicine

Miami Cancer Institute, which is slated to open at the end of 2016, will house the Center for Genomic Medicine. “We analyze genes compared to what is normal. When there is a variation from the norm, it may be interpreted to be a benign genetic variation or a variation associated with increased lifetime cancer risks,” Ordonez said.

A hereditary predisposition to cancer—passed on from parent to child in a mutated gene or genes—accounts for some 10 percent of cancer cases. However, most cancer happens as a result of somatic gene mutations; that is, changes in a gene or genes that occur after conception and are not inherited from a parent. Some of these genetic changes can lead to cancer in a particular organ. Studying that process has led to more-effective, targeted cancer therapies, based on the genetic profile of a patient’s particular tumor.

The Center for Genomic Medicine will focus on the identification of both inherited and somatic mutations.

“By better understanding both bases of cancer,” Ordonez added, “we hope to target medical treatment for patients, improve outcomes and enhance opportunities to prevent cancer.”

top stories

There are no comments